|

Stone, Rob. Spanish Cinema. Inside Film. London: Pearson Education Limited, 2002. ISBN: 0-582-43715-6. Updated on 23 Aug. 2016 Chapter 1: “By Way of Elías Querejeta.” 1-13.

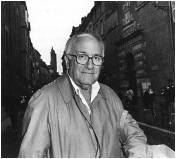

Elías Querejeta was born in October of 1934 in Hernani, in the Basque province of Guipuzcoa. He is a film writer and the most important producer of early Spanish films (until the 1960s). He sponsored films by Carlos Saura, Víctor Erice, Jaime Chávarri, Manuel Gutiérrez Aragón, Ricardo Franco, Montxo Armendáriz, and Julio Medem. In the times of censorship (lifted in 1977 in Spain, two years after the death of General Franco), films became metaphorical in order to criticize the regime from within. At one time (Miró Law, 1983), film-makers in Spain could apply from the government up to 50% of their budget (far in excess of what other European countries granted). But the government of conservative José María Aznar put an end to state subsidies in 1996. Financing increased from private television companies (who invested 5% of their revenue in the making of films) and new companies such as Sogecine. END

Chapter 2: “Leaving the Church.” 14-36. The first Spanish movie was made by Eduardo Jimeno Peromarta & Son in 1896 using a Lumière projector which he had bought in Lyon, France, for 2,500 francs. It was called Salida de la misa de doce del Pilar (Leaving the Midday Mass at the Church of Pilar in Zaragoza). A sequel to this film was made a week later and called Salidas y saludos (Leavings and Greetings). He would charge 30 céntimos (the Spanish national currency at that time, the peseta, consisted of 100 céntimos or “cents”) to show it at his waxworks museum. Louise and August Lumière Eduardo Jimeno Peromarta had seen Alexander Promio’s demonstration of Louise and August Lumière’ cinematographe (kinetofonógrafo in Spanish) [patented on 13 February 1894] in Madrid’s Hotel Rusia in 1896. While L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de la Ciotat (28 December 1895) might have been what the Lumière Brothers found interesting to film, in Spain, Spaniards chose to film Church, school, and royal processions. Hence, the first Spanish films bear titles like: La vista del Campo Valdés tomada a la salida de misa de doce de la iglesia de San Pedro (The View of Campo Valdés taken at the Leaving of Midday Mass at the Church of Saint Peter) [Asturias, 1897]; La salida de misa de doce de la iglesia de Santa Lucía (Leaving the Midday Mass at the Church of Santa Lucía), by Pradero Antigüedad (Cantabria, 1907); Salida de las alumnas del Colegio de San Luis de los Franceses (Pupils Leaving the College of Saint Louis of France), by Alexander Promio (Madrid, 11 May 1896); Viaje de Su Majestad a la Albufera (Voyage of His Majesty to Albufera) [Valencia, 1905]; and Regreso de Su Majestad de la Albufera (Return of His Majesty from Albufera). cinematographe Margarita Xirgu The Catalans (whose capital is Barcelona, in N.E. Spain) were the first film-makers to establish film companies like Hispano Films (established in 1907 by Ricardo de Baños [who studied at the Gaumont Studies in France] and Alberto Marro [a wealthy businessman]). They created the first full-length Spanish features like Don Juan Tenorio, a 1908 adaptation of José Zorrilla’s Romantic play. Hispano Films attracted the major French companies of Pathè, Meliès, and Gaumont, who established their own bases in Barcelona. Another pioneer was Segundo de Chomón, an engineer from Teruel who introduced frame-by-frame filming and the processing and coloring of films like Choque de trenes (Train Crash) [1902], Pulgarcito (Tom Thumb) [1903], and Guliver en el país de los gigantes (Gulliver in the Land of the Giants) [1905]. Chomón was also the first film-maker to actually move the camera during filming. Hence, he is the inventor of the traveling shot. With Joan Fuster Gari, a Barcelona theatrical entrepreneur, Segundo de Chomón established a film studio and created 37 features. In 1913, the Church and the monarchy of King Alfonso XIII decided to establish a censorship body (consisting of the police and Church officials) who had the authority to cut or confiscate film works deemed immoral or with the power to corrupt. In 1920, a law was passed forbidding men and women sitting next to each other in cinemas. The first Spanish serials were done by the Catalans. Some examples are: Joan María Codina’s El signo de la tribu (The Sign of the Tribe), 1915, made by Condal Films; Los misterios de Barcelona (The Barcelona Mysteries), 1915, in 8 episodes, by Hispano Films; El testamento de Diego Rocafort (a six-episode sequel made in 1917). However, the preferred genre was the zarzuela (more than 50% of all Spanish films were zarzuelas). The most famous of all zarzuelas (an opera, actually), was La verbena de la paloma (The Fair of the Dove), done by José Buchs in 1921 (by the company named Atlántida). The first Spanish sound motion picture was Adelqui Millar’s Toda una vida (A Whole Life) [1931], 4 years after The Jazz Singer (1927), the world’s first sound film. Hollywood also produced numerous Spanish-language films (160 between 1930 and 1935) using Mexican and South American casts who would shoot at night using the same sets used during the day for English-language films. Tod Browning’s original Dracula (1931), done by George Melford in Spanish, is considered better than the original on account of its atmospheric and erotic qualities (the Spanish Drácula was discovered in Cuba in 1989 and released in US cinemas in 1992). Intellectuals of the Generation of 1927 (which includes luminaries like the poet Federico García Lorca, the painter Salvador Dalí, and the director Luis Buñuel) valued cinema for its ability to create alternative worlds. Influenced by Fritz Lang and Sergei Eisenstein, Luis Buñuel created the first auteuristic films in Spain, as well as the first critical social commentaries. Un Chien andalous (An Andalusian Dog [1928]), created by Buñuel and Dalí, was a 20-minute feature written in 6 days, shot in 15, and costing 25.000 pesetas (lent by Buñuel’s wealthy mother). This film would revive Surrealism and redefine cinema. It starts as do all fairy tales, but then it takes a nasty turn in its dream-like free association and violence. It also plays with time (flashbacks), double exposures, iris shots, and sundry camera angles. It is also non-sequential and defies cause-effect relationships. The first showing created a riot. His next film was more ambitious, a one-hour long film, L’Age d’Or (The Golden Age [1930]) commissioned by Vicomte Charles de Noailles and Marie Laure (a descendant of the Marquis de Sade). Based loosely on the Marquis de Sade’s Les 120 Journées de Sodome (1785), L’Age d’Or was a surrealist and subversive film with a sequential narrative of sorts that scandalized its audience for its farcical presentation of the bourgeoisie (the military, the nobility, and the Church). The police banned it and Vicomte de Noailles was expelled from the Jockey Club. This film shows a liberated unconscious that enjoys its freedom to sin, very much in the style of Sade and his sadistic characters in Les 120 Journées de Sodome. His next film was Las Hurdes (Tierra sin pan / Land Without Bread [1932]), Buñuel’s first Spanish film and a virulent attack on a selfish society and on man’s inhumanity to man. It had its first screening at the Madrid Prensa Cinema, with Buñuel as narrator. The film was banned in Spain by the Second Spanish Republic. In 1932, Vicente Casanovas set up the Compañía Industrial del Film Español, S. A. (CIFESA), which became the prime exponent of Francoist cinema (escapist and commercially assured films, as well as propaganda films) and the distributor for Columbia Pictures in Spain. In 1935, foreign films in Spain started to be dubbed, replacing the use of subtitling. The 137 films that survived fires and other incidents from 1897 to 1931 are now housed in the Filmoteca Nacional (National Film Institute). They were placed there in 1953. END

Chapter 3: “Under Franco: Spanish Cinema During the Dictatorship.” 37-60. After the collapse of the Bourbon monarchy in Spain and the establishment of a Republic (1931-1936), the Spanish State held on to the film studios in Madrid and Barcelona to make propagandistic newsreels. After the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and the collapse of the Republic, the new State (called National Movement [1939-1975]) appropriated the film industry to make movies of national interest. The National Movement had an interest in happy films that would serve to entertain the people (who had just gone through a bloody Civil War) as well as to educate them in the new nationalist ideology. Hence, some of the film genres were 1) españoladas or andaluzadas (local color films with flamenco skits for national consumption), 2) cine cruzada (celebratory national films), 3) cine de curas (celebratory religious films), and 4) melodramatic morality tales, at times featuring singing prodigies, in which case this sub-genre was called cine con niño (cinema with child). A censorship body was also established to make appropriate cuts or corrections with respect to films that would attack the State, the Church, or public morality. Compañía Industrial de Cine Español, Sociedad Anónima (CIFESA) [Industrial Company of Spanish Film], established in Valencia in 1932 by Vicente Casanovas, served the Nationalist cause alter the Civil War, producing films of national interest like Antonio Román’s Los últimos de Filipinas (1945), about the last stand of Spanish troops in the Philippine Islands in the Spanish-American War (1898). It also produced many newsreels for the National cause. CIFESA was based on Rome’s Cinecittá Studios, established in 1937 to make propaganda films for Premier Benito Mussolini. Under Admiral Carrero Blanco, CIFESA produced several sumptuous films on national history like Locura de amor (1948)—about the madness of Queen Juana, wife of the first Spanish Habsburg monarch in Spain—and Alba de América (1951), about the missionary work of Christopher Columbus in America. After World War II, Italian cinema became Neo-realistic (depressing black and white films shot in urban ghettoes with non-professional actors). Spain followed suit with José Antonio Nieves Conde’s Surcos (Furrows, 1951), which was denounced by the Church.

By 1947, Madrid had established an official film school, the Instituto de Investigaciones y Experiencias Cinematográficas (IIEC) [Institute of Research and Cinematography] which opened with 109 students, among them Juan Antonio Bardem and Luis García Berlanga, who created alternative (oppositional) cinema. Although Bardem had joined the Falange Juvenil (Falange [Spanish Fascist party] Youth) and Berlanga had served in the Blue Division sent to Germany to fight the USSR, they both adopted a political leftist stand early on. UNINCI (Unión Industrial Cinematográfica)

[Cinematographic Idustrial Union], an independent film company formed in

1949 by Francisco Canet Cubel and Ricardo Muñoz Suay (both members

of the clandestine Spanish Communist Party [PCE <Partido Comunista

Español>]) opted to do alternative cinema critical of the National

Movement. One of their famous works was Bienvenido Mister Marshall

(Welcome, Mister Marshall, 1952), a satire on a stagnant Spanish

society. At the Salamanca Congress of 14-19 May 1955 (a film

event), Bardem denounced national cinema as politically useless,

socially false, intellectually base, aesthetically void, and industrially

stunted. He also called for a clarification of the subjective code

of censorship (which then became objective), the protection of Spanish

cinema against an influx of foreign films, the establishment of a national

network of deregulated film clubs, and an appreciation of social realism

in cinema. Bardem’s denunciation attracted wide support from the

right and the left, including José Luis Sáenz de Heredia

(a Falangist film director) and the leftist

Carlos Saura.

Bardem’s subsequent film, Muerte de un ciclista (1955), won the

International Critics’ Prize in Cannes. Another famous Bardem film

was Calle Mayor (Main Street, 1956), co-produced with France.

This second film won the International Critics’ Prize at the Venice Film

Festival and had considerable success in New York.

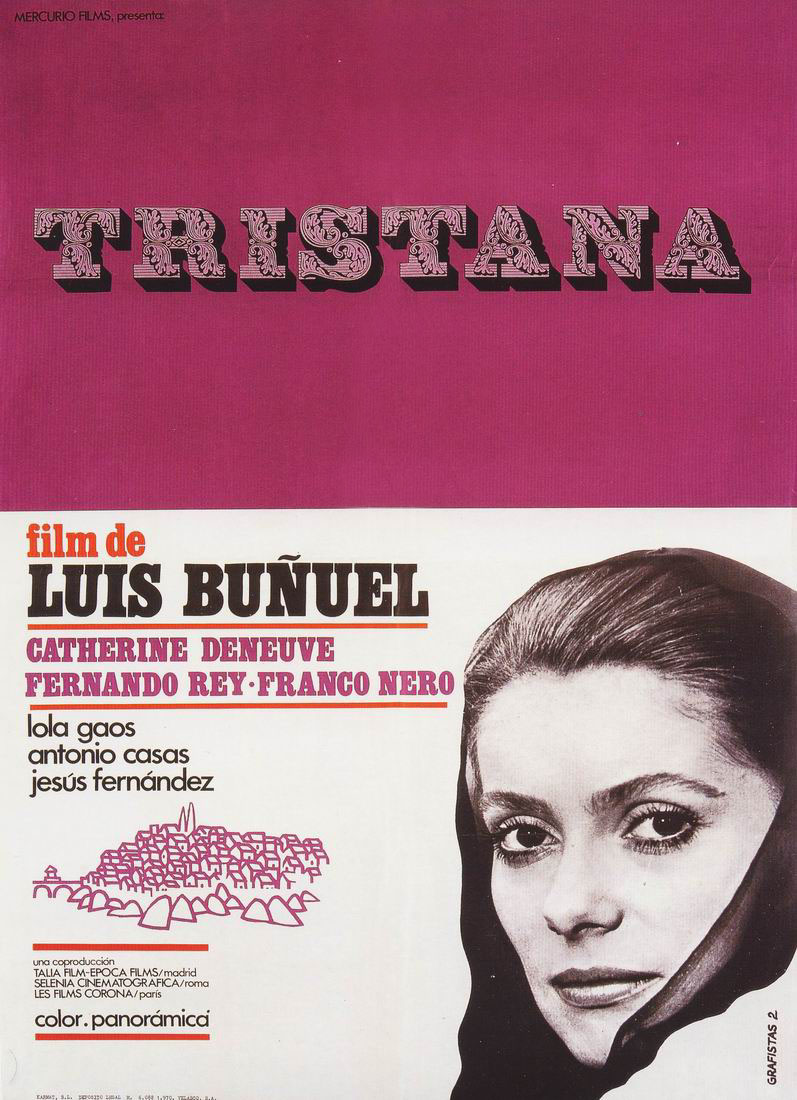

Bardem’s communist stand alienated many critics and producers but got the attention of Luis Buñuel. Buñuel was born in Calanda (Aragón) in 1900 and died in Mexico City in 1983; he went to a Jesuit school, attended the University of Madrid (where he studied agronomy, engineering, and philosophy), and became a friend of poet-dramatist Federico García Lorca and surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, all of them members of the Generation of 27. He moved to Paris in 1925, where he made Un Chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog, 1929, 17 mins., silent), a touchstone of surrealist art. Later he made L’Âge d’or (The Golden Age, 1930, 60 mins., silent [banned in Paris in 1930]), an anti-clerical surrealist film, and Tierra sin pan (Land Without Bread or Las Hurdes, 1932, 27 mins., in French), a film about an impoverished section of Spain. This last film was censored by the liberal Second Spanish Republic. In 1938 Buñuel moved to the US, where he supervised Republican propaganda films and edited documentaries for New York’s Museum of Modern Art. He also worked for Warner Brothers, dubbing films into Spanish. In 1946 he moved to México, where he made some of his most famous films like Los olvidados (1950), Una mujer sin amor (A Woman without Love, 1952), Nazarín (1959), Viridiana (with Silvia Pinal and Fernando Rey, 1961 [banned in Spain from 1961 until 1977]) [which won the Golden Palm at Cannes], El ángel exterminador (The Exterminating Angel, 1962) and Simón de desierto (Simon of the Desert, 1965). He also made excellent films in France (Belle de jour, 1967, with Catherine Deneuve, and La Voie Lactée [The Milky Way], 1969), and Spain (Tristana, with Catherine Deneuve and Fernando Rey, 1970). His last three films were made in France and are among his best: Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972), Le fantôme de la liberté (The Phantom of Liberty, 1974), and Cet obscur objet du désir (That Obscure Object of Desire, 1977). Buñuel joined the Spanish Communist Party (PCE [Partido Comunista Español]) in 1931 and was a highly anticlerical atheist. Always a witty man, however, during a French interview for L'Express (12 May 1960), he stated his famous line «Je suis toujours athée, grâce à Dieu» ("I am still an atheist, thank God"). He is considered a French/Mexican/Spanish director.

END

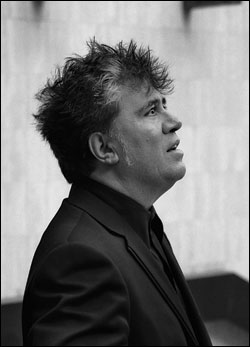

Chapter 4: “Another reality: Carlos Saura.” 61-84. Carlos Saura was born in Huesca (Aragón) in 1932 but lived in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). His parents had been Republican (e.g., socialist, athetist), although his mother remained Catholic. His brother Antonio Saura became a painter and Carlos, who started as an engineer, ended up as a photographer, a journalist, a professor, and the greatest Spanish filmmaker after Luis Buñuel. His first full-length film was Los golfos (The Lotus, 1959), a neo-realistic film with disjointed and open-ended scenes that were reminiscent of French New Wave Cinema.

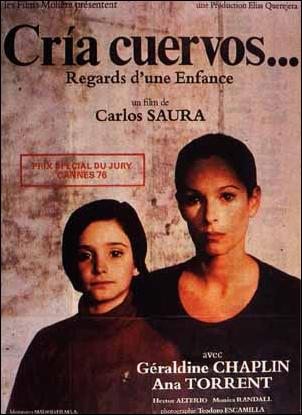

Allegedly, Saura, with the support of producer Elías Querejeta, produced 13 films that attacked Franco ideology. The first would be La caza (The Hunt, 1965), about Nationalist ex-soldiers who go hunting and end up hunting each other down. The film won the 1966 Golden Bear at the Berlin film Festival (Sam Peckinpah apparently liked The Hunt so much that he used it as an influence for The Wild Bunch [1969]). In 1967, Saura meets Geraldine Chaplin (b. 1944), Charles Chaplin’s daughter, and they had a long relationship (personal and professional) that affected Saura’s next ten films. From then on, Saura’s films became less realistic and more intimate, imaginative, psychological, even theatrical. Among his metaphorical works of this period one finds El jardín de las delicias (The Garden of Delights, 1970), about loss of memory and identity. Ana y los lobos (Ana and the Wolves, 1972) became a metaphor for a retrograde Spain controlled by the family, the Church, and the Military. Cría Cuervos (Raise Ravens, 1975) was a film about a traumatized little Ana growing up in a house marked by death. It won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1976.

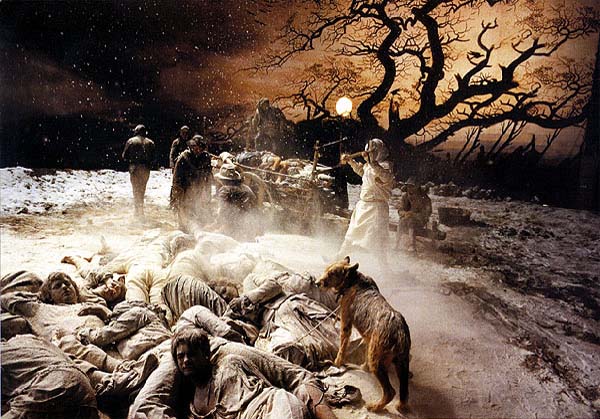

In 1979, Geraldine Chaplin and Carlos Saura’s relationship came to an end. In the 1980s, Saura starts filming works with a Southern (Andalusian) flavor. In them he incorporates dance, ballet, music, and song. He also incorporates more self-conscious cinematography, where the camera or the sets appear as part of the movies he is filming. In this line one finds Bodas de sangre (Blood Wedding, 1981), a potpourri of film, dance, and theater based loosely on Federico García Lorca’s 1933 play of the same name. Another film of this period is Carmen (1983), based on George Bizet’s 19th Century French opera. El amor brujo (Love, the Magician, 1986) was based on the flamenco ballet by Manuel de Falla. With the exception of a political work, ¡Ay Carmela! (1990), Saura continued filming musical works like Sevillanas (1992) and Flamenco (1995). One might placed Tango (1998) in this category as well. He seems to return to political innuendo and social criticism with Goya en Burdeos (Goya in Bourdeaux, 1999). His last film has been Buñuel y la mesa del rey Salomón (Buñuel and King Solomon’s Table, 2001), a homage to his great friend and master, Luis Buñuel.

Goya in Brodeaux END

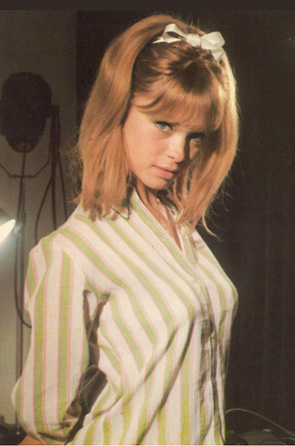

Chapter 5: “Spirits and Secrets: Four Films about Childhood.” 85-109. The alternative viewpoint of children is valued because they are always observing, always questioning, always aware. A number of important children films have been produced in Spain like Víctor Erice’s El espíritu de la colmena (The Spirit of the Beehive) [1973] and El sur (The South) [1983], Carlos Saura’s Cría cuervos (Raise Ravens) [1975), and Montxo Armendáriz’s Secretos del corazón (Secrets of the Heart) [1997]. In these films, children are shown as vulnerable and traumatized by the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), especially if their families belonged to the losing side (The Republican loyalists). However, during the National Movement period (1939-1975), especially in the 1950s and 196s, the Nationalist cinema presented children as precocious and happy-go-lucky, singing beings. Some of these children actors were Pablito Calvo, of Marcelino, pan y vino (Marcelino, Bread, and Wine) [1954], a religious and inspirational work; the singing actor Miguelito Gil, of El pequeño ruiseñor (The Little Nightingale) [1956], whose rural ambition is to have a family; and the singing young actress «Marisol» (Pepa Flores), an 11 year-old blonde and blue-eyed Hayley Mills type who starred in films like Ha llegado un ángel (An Angel Has Arrived) [1961] and Tómbola (1962), and who was General Franco’s favorite actress. Little Pepa Flores eventually grew up and posed nude in the magazine Interviu. She also married the dancer Antonio Gades and appeared in Carlos Saura’s Bodas de sangre (1981) and Carmen (1983). Spanish Children Actors:

Víctor Erice’s El espíritu de la colmena (The Spirit of the Beehive) [1973]: Víctor Erice was born in the Basque province of Vizcaya in 1940 and graduated from Madrid’s Official Film School in 1963, where he studied under Carlos Saura. According to some critics, El espíritu de la colmena (The Spirit of the Beehive) [1973] is the undisputed masterpiece of Spanish cinema. It is the story of little Ana (Ana Torrent), whose innocence enables her to befriend an anarchist fugitive who is eventually discovered and executed by the Civil Guards. This traumatizes the little girl, who at the end of the film is shown as likely to recover as time goes by. This film was seen as critical of the National Movement and had a mixed reception in Spain. It received a Golden Shell (the equivalent of a Cannes Golden Palm, a Berlin Golden Bear, a Mexican Ariel, or a Hollwyood Oscar) at the San Sebastián Film Festival in Spain, although it was roundly booed by a considerable part of the public. Víctor Erice has made only two other movies: El sur (The South) [1983] and El sol del membrillo (The Quince Tree Sun) [1992]. Carlos Saura’s Cría cuervos (Raise Ravens) [1975]: Carlos Saura does not glorify childhood. On the contrary, he views it as a painful growing up process. Cría cuervos (Raise Ravens) [1975] deals with the little girl Ana (Ana Torrent), whose father was a Falangist (Spanish Fascist) soldier and whose mother (Geraldine Chaplin) is dead. In her solitude and sadness, Ana daydreams about her mother, who appears to her from time to time to comfort her. It is a sad film. Montxo Armendáriz’s Secretos del corazón (Secrets of the Heart) [1997]: This is the story of a little boy, Javi. Other films of childhood are Juanma Bajo Ullosa’s Alas de mariposa (Butterfly Wings) [1991], close to a gothic horror film; Arantxa Lazcano’s Los años oscuros (The Dark Years) [1993]; Maité (1995), a Basque-Cuban co-production; Carlos Saura’s Pajarico (1997); and José Luis Cuerda’s La lengua de las mariposas (Butterfly) [1999], about a child in a pre-Civil War Galician countryside, son of a Catholic mother and a Republican father, who is forced to betray the wise old village teacher whose crime was to be a Republican (Socialist) at the time the Falangist forces are arriving in Galicia; and Montxo Armendáriz’s 27 horas (27 Hours) [1986] and Historias del Kronen (Stories from the Kronen) [1994], about drug-addled Spanish youth. END

Chapter 6: “Over Franco: Spanish Cinema in Transition.” 110-132. General Francisco Franco, Chief of State (Jefe de estado) during the National Movement (1939-1975), died on 29 November, 1975. Spain had already restored the Bourbon monarchy, so Prince Juan Carlos became King Juan Carlos I. Adolfo Suárez, ex-Secretary General of the National Movement, was appointed Prime Minister in 1976 and thus started Spain’s Transitional Period (La transición) to what Spaniards referred as the “new democracy,” which was simply a return to the constitutional monarchy that had been abrogated by the Spanish Second Republic, interrupted by the Civil War, and put on hold during the interim period known as the National Movement. Censorship was revoked by royal decree on November of 1978. Hence, former categories like “special interest” films, which had allowed auteurs like Carlos Saura to flourish during Franco’s regime, were withdrawn. Previously forbidden films were shown for the first time in Spain like Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), and Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana (1961). Co-productions flourished as well under this period (the 1970s), especially with Italy and South America. New genres were also created like the paella western, the policíaca (brutal, urban thrillers), and soft-core pornography (destape). Quality filmmakers engaged in some of these commercial genres, but stretching or subverting the rules of these kinds of films. The Barcelona School became at this time a respectful

institution that competed with the Madrid Official Film School.

After Catalonia (the province of which Barcelona is the capital) declared

its autonomy in 1977, the Barcelona School became experimental and

more attuned to the French New Wave. Being wealthier than the Castilians,

the Catalans took to the sub-genres of fantasy, horror, and sex comedy,

but revamping them. Vicente Aranda was (is) the most important

figure of this generation.

Vicente Aranda was born in Huesca (Province of Aragón, just west of Catalonia, at one time constituting a united kingdom) in 1937 but his family moved to Barcelona during the Civil War. He never finished his studies and was rejected at the Madrid Official Film School. His wealth, however, enabled him to travel to Venezuela and to start making films. He started as a Neo-realist with Brillante porvenir (1964), a co-production, and later directed a comic spy thriller, Fata Morgana (1966) and two horror/vampire films, El cadáver exquisito (The Exquisite Corpse [1969]) and La novia ensangrentada (The Bloody Bride [1972]). Eventually he moved to social criticism and other shocking themes in Cambio de sexo (Change of Sex [1976]), starting Bibi Anderson (Pedro Almodóvar’s good friend [Bibi is a man]) and Victoria Abril (Spain’s best paid and most popular actress) and La muchacha de las bragas de oro (The Girl in the Golden Panties [1979]). He also made a policíaca, Asesinato en el Comité Central (Murder in the Central Committee [1982]) and the erotic thriller Amantes (Lovers), starring Victoria Abril and Maribel Verdú (the actress of Y tu mama también). Other films of his are Intruso (Intruder [1993]) and El amante bilingüe (The Bilingual Lover [1993]), La pasión turca (The Turkish Passion [1994]), and Libertarias (1996). Three Famous Spanish Actresses:

Sarcastic comedies with social criticism were directed by the seemingly immortal Luis García Berlanga (1921- ): La vaquilla (The Little Bull [1984]). Other “vulgar comedies” (comedias zafias) were made by Manuel Gómez Pereira’s ¿Por qué lo llaman amor cuando quieren decir sexo? (Why Do They Call It Love When They Mean Sex? [1992]) and Todos los hombres sois iguales (All You Men Are the Same [1993]). These were so-called Tercer vía films (comedies with social messages). More sophisticated comedies of manners were called comedias madrileñas (Madrid comedies). Some important auteurs were Fernando Colomo and José Luis Garcí. Colomo’s Tigres de papel (Paper Tigers [1977]) celebrated the replacement of an archaic bourgeois morality with youthful liberalism and became one of the first major successes of the new democracy. José Luis Garcí, director of Asignatura pendiente (Subject Pending [1977]), Solos en la madrugada (Alone in the Early Hours [1978]), and Volver a empezar (To Begin Again [1981]), won Spain’s first Academy Award (the Oscar) for best foreign language film. Other important directors are Fernando Trueba, director of Ópera prima (1980) and also winner of another Oscar for his Belle époque (1992), about life in Spain before the Civil War; and Pilar Miró, director of El crimen de Cuenca (The Cuenca Crime [1979]), which offended the Civil Guard and caused the director to face a military trial. The case against her was later transferred to a Civil Court and dismissed. Pilar MIró formed part of the socialist government of Prime Minister Felipe González in 1982. In that capacity she revised the distribution of government funding for film and was instrumental in the creation of so-called X theaters, which now legally show hard-core pornography in Madrid. She was also head of RTVE (Radio y Televisión Española [Spanish Radio and Television]). Three Famous Spanish Directors:

When Pedro Almodóvar (La Mancha [province of Castile], 1949- ) comes to the scene, he in effect avoided stereotypes of the police and the Civil Guard and simply realigned them as often unwitting accomplices in his farces. This reconciliation on Almodóvar’s part of the old regime, as well as his mixtures of the old and the new in his films, his affectionate satires, his apolitical stance in all his movies, his compassion for the marginalized, and his surprisingly old-fashioned traditional values, have made him a favorite son of Spain and, it seems, the world. A great director nowadays is José Luis Cuerda, who made La lengua de las mariposas (Butterfly [1999]). The leading auteurs of the moment in Spain are Julio Medem (San Sebastián [Basque Province], 1958- ), director of Los amantes del círculo polar (Lovers of the Arctic Circle [1998]) and Lucía y el sexo (Sex and Lucia [2001]) and Alejandro Amenábar (born in Santiago, Chile, 1972- ), director of Tesis (Thesis [Snuff] <1996>), Abre los ojos (Open Your Eyes [1997]), Los otros (The Others [2001]), and Mar adentro (The Sea Inside [2004]). Three famous Spanish auteurs:

END

Chapter 7: "An Independent Style: Basque Cinema and Imanol Uribe." 133-157. The indigenous production of fictional shorts began in 1923 in the Basque Province with the appearance of Hispania Films in Bilbao. Thanks to the efforts of the zine-klubs (private film societies), the San Sebastián Film Festival was founded in 1953. New production companies emerged in the 1970s like Bertan Filmeak and Araba Films. Imanol Uribe was born in San Salvador in 1950 to Basque parents. He studied under Pilar Miró and made his first full-length documentary called El proceso de Burgos (The Burgos Trial, 1979), a political film, just prior to the declaration of autonomy of the Basque Country in 1979. At that time, the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV) dedicated 5% of its budget to the the film industry to promote Basque culture. The subsidies provided by the PNV did not have to be repaid. Movies like Uribe’s La fuga de Segovia (The Segovia Breakout, 1981), Alfonso Hungría’s La conquista de Albania (The Conquest of Albania, 1983), and Pedro Olea’s Akelarre (1983) were made with PNV subsidies. In 1991, the PNV set aside 80 million pesetas to produce 7 films.  A Navarra filmmaker, Montxo Armendáriz, born in 1949, has made films like Tasio (1984), a naturalistic portrait of a charcoal burner. He also made a film about Senegalese immigrants to Spain in Las cartas de Alou (Alou’s Letters, 1990) and Historias del Kronen (Stories from the Kronen). His Secretos del corazón (Secrets of the Heart, 1997) is a film about children. Many directors who had received funding from the PNV in the 1970s created their own production companies in the 1980s. Hence, independent filmmaking flourished as a result. Imanol Uribe created Aiete Films and made La muerte de Mikel (Mikel’s Death, 1983), a political film, and then moved to film noir with Adiós, pequeña (1986) and horror films (La luna negra, 1989). He also made El rey pasmado (The Dumbfounded King, 1991) and Días contados (Running out of Time, 1994). Four Basque Directors:

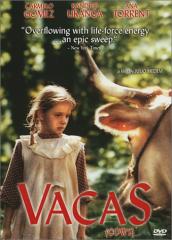

Other Basque filmmakers are Álex de la Iglesia, born in Bilbao in 1965, and inspired by comic books. El día de la bestia (The Day of the Beast, 1995) is an elaborate satire on neo-fascist elements of Spanish culture. This film was a great commercial success. Another Basque filmmaker, Juanma Bajo Ulloa (Vitoria, 1967), has made excellent women’s films like Alas de mariposa (Butterfly Wings, 1991) and La madre muerta (The Dead Mother, 1993). These films are not political. Contemporary Basque directors of the 1990s are Julio Medem and Daniel Calparsoro. Medem subverts the rural genre with Vacas (Cows, 1991) and La ardilla roja (The Red Squirrel, 1993). Calparsoro has dealt more with urban issues in Salto al vacío (Jump into the Void, 1995), which deals with marginalization and urban alienation. END

Chapter 8: "Projections of Desire: Julio Medem." 158-182. Julio Medem was born in 1958 in San Sebastián (Basque Province), Spain. He is the son of a Basque-French designer mother and a German draughtsman father. He has a sister named Ana. He studied psychiatry and eventually got a degree in medicine and general surgery. He criticized the previous generation of filmmakers for placing political intent above artistic considerations. He also belongs to a generation that sees Pedro Almodóvar as an embarrassing “father” figure (on account of his excesses). Julio Medem’s movies (e.g., Vacas [Cows], 1992; La ardilla roja [The Red Squirrel], 1993; Tierra [Earth], 1996, and Los amantes del círculo polar [Lovers of the Arctic Circle], 1998) have amassed awards and effusive praise in international festivals and markets for their striking images and ideas, establising Medem as the leading light in contemporary Spanish filmmakers. He uses the camera to focus on dilemmas of duality, chance encounters, fateful symmetry, and a body-and-soul divide, while incest, amnesia, schizophrenia, and death are just a few aspects of the human condition that he treats with a sensuality expressed in colors, camera-work, and editing. Desire is the driving force of Medem’s films. He also used a 1985 PNV budget of 3 million pesetas to found Grupo Delfilm, a production company. Julio Medem's Films:

Vacas (Cows), 1992: The film Vacas is divided into 4 chapters that cover a period from the end of the Second Carlist War in 1885 to the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. In this film, as well as in Medem’s other films, the complicity between females and nature is a dominant theme. The film also rejects certain stereotypes or expectations of a “Basque” film, for Medem sees incest, like civil war, as the enemy within the Basque mentality. War between brothers is as immoral and self-destructive as sex with sisters. Medem also suggests that the Basque pride in racial purity as enshrined in the writings of Sabino Arana (the founding father of Basque nationalism, who died in 1903 at the age of 38) was the primary cause of the wars and intermarriage that seeded their own stagnation. The reunion of mismatched lovers forms the conclusion of all of Medem’s films. La ardilla roja (The Red Squirrel), 1993: Like Vacas, La ardilla roja is a parody of mythic origins that deals with constructed notions of self. This seems to be a chaotic film, both visually and narratively. Tierra (Earth), 1996: This is the story of Ángel (Carmelo Gómez), who cannot decide between two women: trusting Ángela (Emma Suárez) or lusting Mari (Silke). He finally opts for Mari. Los amantes del círculo polar (Lovers of the Arctic Circle), 1998: This is a fragile and tender love story about two lovers bound by symmetrical repetitions in time and space, as well as chance. Ana is played by Najwa Nimri. Otto is played by Fele Martínez. This movie took 9 weeks of filming and 7 months of editing. The movie has two separate endings. Julio Medem is liked and admired by Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg. END Chapter 9: "Seeing Stars: Banderas, Abril, Bardem, Cruz." 183-205. Censorship in Spain during the National Movement (1939-1975) period was highly moral. At that time in Spain there was also no divorce (in 1981 it became legal), no abortion (legal in 1985), and no contraceptives (legal in 1981). Adultery, likewise, was a criminal act (it was decriminalized in 1978). After censorship was revoked by royal decree in 1977, there was a destape or uncovering of all taboos; subsequently, sex became a commodity. Apart from pornography, some of the most erotic quality films in Spain after the destape were Pedro Almodóvar’s ¡Átame! (Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down, 1989), Vicente Aranda’s Amantes (Lovers, 1991), Juan José Bigas Luna’s Jamón, jamón (Ham, 1992), and Alejandro Amenábar’s Abre los ojos (Open Your Eyes, 1997). Actors and actresses like Antonio Banderas, Victoria Abril, Javier Bardem, and Penélope Cruz, became sex symbols in Spain and abroad.

Antonio Banderas: Antonio Banderas was born in Málaga in 1960 and christened José Domínguez. He was a student of dramatic arts and Imanol Arias, a friend, suggested his name to Pedro Almodóvar, who gave him a new name and used him in several of his films: Laberinto de pasiones (Labyrinth of Passion, 1982), La ley del deseo (The Law of Desire, 1987), ¡Átame! (Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down, 1989), and Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, 1988). Banderas is known for his quick wit, his charisma as an actor, his energy and magnetism, his athletic build, his clean-cut masculinity, and his lack of inhibition. Madonna, the material girl, singled Banderas out as the sexiest man alive. Subsequently he moved to Hollywood, married Melanie Griffith, and starred in films like Mambo Kings (1991), Philadelphia (1993), Desperado (1995), Assassins (1995), and The Mask of Zorro (1998). Victoria Abril: Victoria Abril was born in Madrid in 1959. As a child she studied classical ballet and married her Chilean agent when aged just 15. She has a throaty voice, a raucous laugh, and a sweet smile. She is also, in her words, 80% organic and 20% cerebral. She plays highly charged erotic and psychological intense characters. She was discovered by Catalan director Vicente Aranda, who used her in Cambio de sexo (Change of Sex, 1977), La muchacha de las bragas de oro (The Girl in the Golden Panties, 1979), Si te dicen que caí (1989), and Amantes (Lovers, 1991) [opposite Jorge Sanz and Maribel Verdú], which earned her an award for best actress at the Berlin Film Festival. As Luisa in Amantes, Victoria Abril was sexual, urban, active, and sadistic. She also stared in several Almodóvar films like ¡Átame! (opposite Antonio Banderas) and Tacones lejanos (High Heels, 1991) (opposite Miguel Bosé and Marisa Paredes). She has starred in foreign films like Josianne Balasko’s Gazon Maudit (French Twist, 1994). In real life, Victoria Abril is restless and uninhibited. Javier Bardem: Javier Bardem was born in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, Spain, in 1969. He is the son of actress Pilar Bardem and the nephew of the director Juan Antonio Bardem. He is intelligent, has a strapping physique, a bashed-in nose, and sad-looking eyes. He was discovered by director Juan José Bigas Luna, who used Bardem in several of his films like Jamón, jamón (1992) [opposite a 16-year old Penélope Cruz], Huevos de oro (Golden Balls, 1993), La teta y la luna (The Tit and the Moon, 1994), Bilbao (1978), Caniche (1979), Lola(1985), and Las edades of Lulú (The Ages of Lulu, 1990) [opposite Italian actress Francesca Neri], a film based on a pornographic novel by the same name written by Almudena Grandes. He has also appeared in Vicente Aranda’s El amante bilingüe (The Bilingual Lover, 1993), Almodóvar’s Carne trémula (Live Flesh, 1997), Álex de la Iglesia’s Perdita Durango (1997), Julian Schnabel’s Before Night Falls (2000), and Alejandro Amenábar’s Mar adentro (The Sea Inside, 2004). Penélope Cruz: Penélope Cruz was born in Madrid in 1974. She studied classical and Spanish dance and worked as a model and presenter on children’s television before playing a role in Bigas Luna’s Jamón, jamón at age 16. She also starred in Fernando Trueba’s Belle epoque and La niña de tus ojos (The Girl of Your Dreams, 1999), Almodóvar’s Carne trémula (1997) and Todo sobre mi madre (1999), and Alejandro Amenábar’s Abre los ojos (1997) [opposite Eduardo Noriega]. In Hollywood she has played opposite Tom Cruise in Vanilla Sky (2001), a remake of Abre los ojos), All the Pretty Horses, Captain Correlli’s Mandolin, and Woman on Top (2001). Recently, Penélope Cruz has also starred in Italian director Segio Castellitto’s Non ti muovere (Don’t Move, 2004). Other (24) great Spanish actors and actresses are:

Page Created by: A. Robert Lauer

arlauer@ou.edu |