|

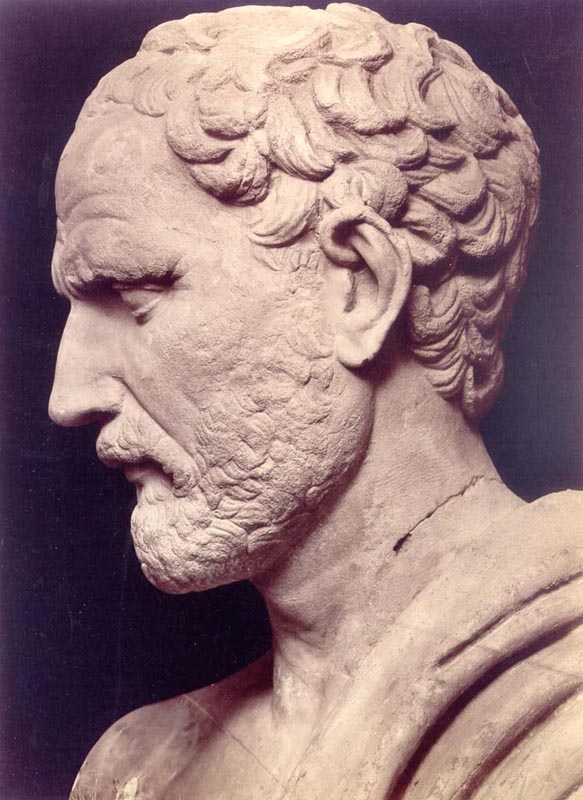

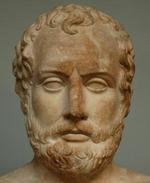

DEMOSTHENES

(384-322 BC):

Demostehenes

Demosthenes

was born in Athens in 384 and died in the island of Poros

in 322 BC. He is considered the perfect orator (by Cicero).

He was a professional speech writer (a logographer), a lawyer, a statesman,

and even an actor. Politically he remained steadfast in his defense

of Athenian liberty and democratic government. Hence, he opposed

the expansionist and centralist policies of King Philip II (359-336

BC) of the northern Kingdom of Macedonia, as well as the imperialist

policies of his son Alexander the Great (336-323 BC). Demosthenes'

speeches cost Athens dearly, for they merely prolonged Philip II's ambitions

to conquer the entire city-states of Greece. However, he never lost

the support or the love of the Athenians. In 336 BC, an orator

named Ctesiphon proposed to honor Demosthenes with the bestowal

of a golden crown for his virtue (services to the state).

Another famous orator and statesman, Aeschines (389-314 BC), a pragmatist

who had previously been won over by Philip II and, consequently, was attacked

and denounced by Demosthenes, opposed Ctesiphon's proposal on three legal

grounds. In his famous speech Against Ctesiphon, Aeschines

claimed that Ctesiphon's motion was illegal because: 1) The Code of

Solon forbade crowning a public official until the expiration of his

term in office (and Demosthenes had been commissioned at that time to repair

the walls of the city and to supervise the Dionysian Festival Funds); 2)

The law prescribed that golden crowns could only be bestowed by the city

in a public assembly on the Pnyx (a hill in Athens where the Ecclesia

[assembly of the democracy of ancient Athens] met) [Ctesiphon had suggested

that the crown be bestowed at the theater on the occasion of the new tragedies

of the Dionysia], and 3) Ctesiphon had brought false statements

in his motion by asserting that Demosthenes had always been a patriotic

and useful citizen. At this time, Thebes and Sparta

had been destroyed by Alexander; hence, to honor Demosthenes (who had opposed

Philip and Alexander) would have angered the new powers even more than

necessary. The motion was delayed for six years. When

it was finally brought to court in August, 330 BC (to a jury of

500 Athenian citizens), Demosthenes responded with his most famous judicial

speech, On the Crown. Aeschines, the prosecutor, lost the

case (he failed to get the votes of 1/5 of the jury). A year later

Demosthenes received his crown and Aeschines, who suffered opprobrium,

moved to Rhodes, where he founded a school of rhetoric (Aeschines,

like Demosthenes, belongs to Greece's "Alexandrian Canon" or the

"Canon of Ten" Attic Orators, a list of the greatest orators of

Greece's classical period [510-323 BC or 187 years], which includes Isocarates

and Isaeus, two of Demosthenes' teachers]), and later to Samos,

where he died. In his private life, Demosthenes seems to have been

at times corrupt (he apparently took bribes and was guilty of larceny),

was a somewhat opportunistic pederast (he used wealthy boy lovers for their

money), and a cowardly man in matters of war (he was accused of desertion).

After Alexander's death, Antipater, his successor, requested the

rendition of Demosthenes. The Athenian Ecclesia subsequently

condemned anti-Macedonians agitators to death. Demosthenes escaped

to Poros and, upon being found, committed suicide by poison.

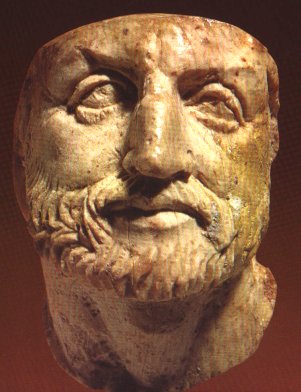

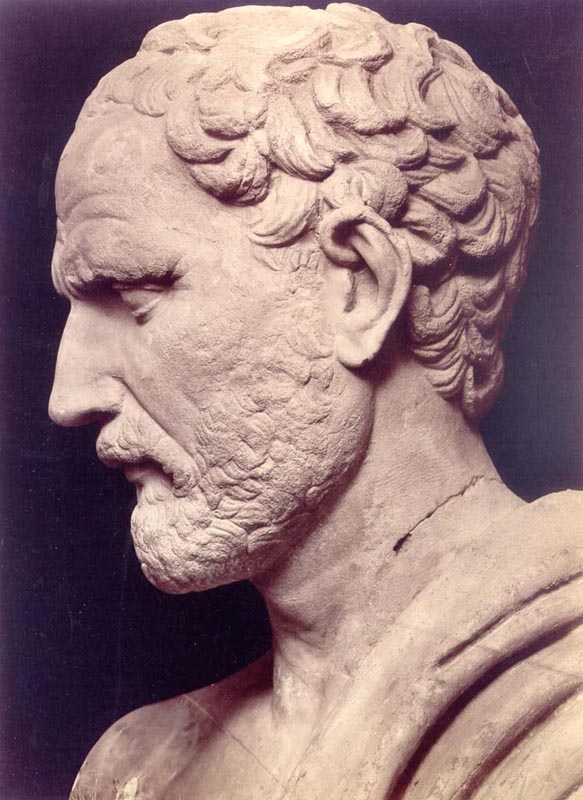

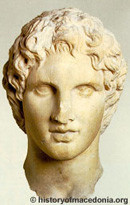

Aeschines.

British Museum. London.

DE CORONA (ON THE CROWN)

[330 BC]:

EXORDIUM (pp. 1-8):

Notice the many

instances of captatio benevolentiae: "Men of Athens."

He seeks "benevolence towards me." Demosthenes prays for the

Atehnians, their conscience, and their honor. Demosthenes discusses

the impartial hearing, the lack of prejudice. Demosthenes asks that

he be granted the favor of arranging his speech according to his discretion

and judgment. He fears loss of favor, kindness, and goodwill.

He is concerned equally with Ctesiphon in these proceedings.

He asks to be listened to and for them to proceed with justice.

He appeals to Solon, "a good democrat and friend of the people."

He alludes to the calumnies of the prosecutor (Aeschines).

PROTEST AGAINST IRRELEVANT CHARGES (p. 9):

Aeschines has brought

false accusations and irrelevant topics.

REPLY TO CHARGES AGAINST PRIVATE LIFE (pp. 10,

11):

Demosthenes will

give an honest and straightforward reply. He is also a better man

and better born.

INTRODUCTION TO DISCUSSION OF PUBLIC POLICY (pp.

12-17):

Aeschines has brought

malicious charges, denouncing him, Demosthenes, but indicting Ctesiphon.

Aeschines' accusations are dishonest and untruthful, reflecting more the

prosecutor's faults than Demosthenes' crimes.

FIRST PERIOD: THE PEACE OF PHILOCRATES (346

BC) [pp. 18-52]:

Allusion to the

Phocian

War (355–346 BC), which ended with Philip II's destruction of Phocis.

Phocis, Thebes, and other Greek city-states were experiencing

strife and confusion. Philip II of Macedonia observed those

conditions, bribed traitors, and tried to promote embroilment and disorder.

The Thessalians and Thebans saw Philip II as their friend,

benefactor, and deliverer. Demosthenes opposed Philip II,

but Aeschines did not, nor did he oppose Demosthenes. Now he bewails

the fate of those city-states that have lost their independence.

But no more should be said of this matter (notice the aposiopesis).

INTRODUCTION TO CHARGES RELEVANT TO THE INDICTMENT

(pp. 53-59):

Demosthenes reads

Aeschines' indictment against Ctesiphon (whom Demosthenes is defending):

1)

It is false that Demosthenes has consistently shown good will to Athenians

and Greeks to merit a golden crown. 2) It is illegal to crown

someone subject to audit (Demosthenes was then Commissioner of Fortifications

and a trustee of the Theatrical Fund). 3) It is illegal to

crown someone at the Theater of the Dionysia instead of the Council-house

(the Ecclesia) on the Pnyx.

SECOND PERIOD: THE RENEWAL OF WAR (340 BC) [pp.

60-109]:

Demosthenes asks

Aeschines what the duty of Athens was when she perceived that Philip's

purpose was to establish a despotic empire over all Greece. Philip

was committing injustices, breaking treaties, and violating the terms of

peace. He, Demosthenes, stood in his way and warned and admonished

the Greeks to surrender nothing. And yet, the peace was broken (and

not by Athens) when Philip seized some merchant men. The People resolved

to send ambassadors to Philip concerning the removal of the vessels (which

Philip eventually lets go). However, even he, Philip, did not blame

Demosthenes in respect to the war (although the king blames others).

As far as the crown is concerned, Demosthenes says no dishonor, contempt,

or ridicule has befallen the city. The decree shows the gratitude

of Athens to Demosthenes, not censure. Philip then tried to control

the carrying trade in corn, which the Athenians consume in greater quantities

than other nations. Demosthenes is proud of his refusal to compromise.

Demosthenes has maintained the same character in domestic and Hellenic

affairs. At home he never preferred the gratitude of the rich to

the claims of the poor; in foreign affairs he never coveted the gifts and

friendship of Philip rather than the common interests of all Greece.

REPLY TO THE TWO MINOR COUNTS (pp. 110-25):

Demosthenes has

created good policies and has been the people's friend. It should

perhaps be illegal for men holding office in government to make presents

to the government. Demosthenes held office and was audited for his

offices though not for his gifts (which he had given the state in the form

of a donation). Demosthenes reads a decree where he is commended

for his donations; yet that is not mentioned in the indictment. Acceptance

of gifts, hence, is legal (like Demosthenes giving donations to the state),

but gratitude for gifts is illegal and grounds for indictment. Aeschines

is dishonest and malignant. Aeschines should be ashamed for prosecuting

for spite, not for crime. An accusation implies crimes punishable

by law. Is Aeschines the enemy of Athens or of Demosthenes?

Aeschines poses as Demosthenes's enemy, but is he not the enemy of the

people?

ATTACK ON THE PRIVATE CHARACTER OF AESCHINES (pp.

126-31):

Aeschines

is the son of Tromes, a slave. His mother Glaucothea

was not as the Banshee for the pleasing diversity of her acts and

experiences. Aeschines was raised from servitude to freedom by the

favor of his fellow-citizens, whom he has betrayed to the enemy, to their

detriment.

ATTACK ON THE PUBLIC MISDEEDS OF AESCHINES (pp.

132-38):

Demosthenes reads

a decree wherein is stated that Aeschines came at night to the house of

Thraso

to communicate with Anaxinus, a proven spy from Philip II of

Macedon. Aeschines is helping the enemy and maligning him, Demosthenes!

Demosthenes says he omits thousands of stories he could tell about him

(notice the paralipsis or ocultatio).

ATTACK ON AESCHINES' PROVOCATION OF THE AMPHISSIAN

WAR (339 BC) [pp. 139-59]:

Demosthenes states

that by false reports, Aeschines contrived the destruction of the Phocians.

The war at Amphissa that brought Philip to Elatea and ruin

to Greece was also caused by Aeschines. Demosthenes protested to

no avail. Philip needed to make Thebes and Thessaly

the enemies of Athens. Philip hired (bribed) Aeschines

as his Athenian representative to carry out his conquests with Aeschines's

favor. War against the Amphissians was provoked. Aeschines

is responsible for providing Philip with the right pretexts to invade and

destroy the Greeks. Do not blame Philip alone, but all the other

traitors from the city-states who sided with Philip, including Aeschines

THIRD PERIOD: THE BATTLE OF CHAERONEIA (338 BC)

[pp. 160-87]:

The Battle of

Chaeroneia (338 BC) was fought between Philip II of Macedonia

and an alliance of sundry Greek city-states, the principal being Athens

and Thebes. It resulted in a decisive victory for Philip

and Macedonia. Demosthenes claims that he alone among Athens'

orators did not desert the post of patriotism in the hour of peril.

Demosthenes suggested an alliance between Thebes and Athens,

since the Athenians and the Thebans have always had good relations.

Demosthenes' suggestion was applauded and followed.

GENERAL DEFENSE OF THE ATHENIAN POLICY OF RESISTANCE

(pp. 188-210):

Demosthenes states

that he should not be accused of crime because Philip won the battle, for

the event was in God's hands, not his. Demosthenes' deliberation

then (to unite with Thebes against Philip) was a sound and honorable one.

Things might have been worse if Athens had fought alone or if Thebes had

sided with Philip against Athens. If Aeschines had not approved of

this policy then he should have spoken, but he didn't. Demosthenes

behaved honorably; Aeschines did not. Demosthenes' deliberation was

unanimously approved by the Athenians, also. Hence, Aeschines's attack

on Demosthenes is also an attack on all Athenians. And even if Aeschines

had suggested a different policy (one of conciliation or alliance with

Philip), Athens would have followed the honorable course. Had Athens

sided with Philip she would have betrayed Greece and freedom. But

that is not part of Greek character (servility or betrayal). To condemn

Ctesiphon for suggesting that the Greeks should honor an honorable man

(Demosthenes) would be tantamount to condemning all Greece.

THIRD PERIOD RESUMED (pp. 211-51):

The Athenians assisted

the Thebans, and, hence, war damages did not ensue to Athens. Philip

is a despotic ruler and an autocrat. Demosthenes' only weapon to

defy Philip was his public speaking, by which he created alliances between

Athens

and the Euboeans, Achaeans, Corinthians,

Thebans,

Megarians,

Leucadians,

and Corcyraeans. They provided 15,000 infantry

and 2,000 cavalry, not counting the citizen-soldiery.

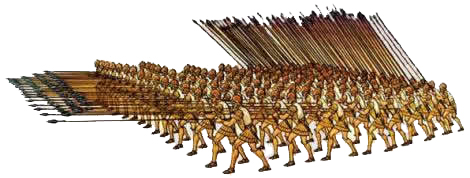

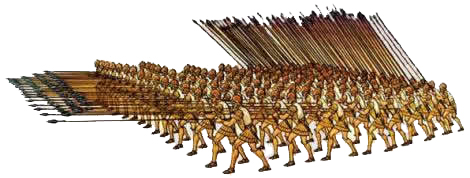

[NB: Philip II's phalanx formation consisted of 16,384 soldiers].

And Athens contributed twice as much than anybody else to the common deliverance.

Demosthenes also was sent as a representative to talk to Philip, but he

was not corrupted by him, as was Aeschines. Philip was successful

on account of his superior army, his bribery of ambassadors, and his corrupting

of politicians. Demosthenes did his job as ambassador honestly and

without corruption.

RENEWED ATTACK ON THE LIFE AND CHARACTER OF AESCHINES

(pp. 252-75):

Demosthenes believes

it is a stupid thing to reproach one's fellow man on the score of fortune.

Demosthenes claims that in his boyhood, he, Demosthenes, had the advantage

of attending respectable schools. When he came of age, his circumstances

were in accordance with his upbringing. He rendered good service

to the commonwealth. Even his enemies thought he, Demosthenes, was

honorable. But Aeschines was born in abject poverty and not holding

the position at first of a free-born boy. He was a clerk and errand-boy

to minor officials. But Demosthenes will omit other things about

Aeschines's life so as not to discredit himself. Aeschines has served

the enemies of Greece; Demosthenes has served his country. In private

life, Demosthenes has been generous and courteous, has ransomed captives

and provided dowries as a matter of principle. Fate can overturn

good intentions and honorable causes; yet, Aeschines is savage and malignant

in turning misadventures into crimes.

REPLY TO THE IMPUTATION OF RHETORICAL ARTFULNESS

(pp. 276-84):

Demosthenes has

exercised his skill in speaking on public concerns and for the advantage

of the Greeks, not on private occasions and for their detriment.

But Aeschines is peevish and seems to have gone to school not to get satisfaction

for any transgression but to make a display of his oratory and vocal powers.

But

diction and vigor are of no value if they are not used to support the policies

of the people. As soon as Philip won the war, Aeschines went

to see him and sided against the interests of his countrymen. Who

is then the traitor?

CLAIM THAT THE ORATOR'S PUBLIC ACTS HAD ALREADY RECEIVED

THE APPROVAL OF THE PEOPLE (pp. 285-96):

When the city wanted

a speaker to honor the slain soldiers at war, they chose Demosthenes over

Aeschines. Moreover, Aeschines when he recounted the disasters that

befell the city of Athens, expressed no feelings and shed no tears.

Thus he showed his inability to sympathize with the sorrows of the common

people. People like Aeschines and his followers are traitors and

sycophants who measure their happiness by their belly and baser parts while

they betray forever the freedom and independence of the Greeks.

EPILOGUE AND RECAPITULATION (pp. 297-323):

Demosthenes has

been upright, honest, and incorruptible. He administered in all purity

and righteousness. He built fortifications for the protection of

the city and made provision for the passage of corn-supply. If fate

intervened against the destiny of Athens, is he, Demosthenes guilty?

Had fate intervened positively, Demosthenes' policies would have brought

the country's well-being, alliances, revenues, commerce, and good legislation.

But what alliances does Athens owe to Aeschines? What war-galleys,

or munitions, or fortifications? "Of what use in the wide world are

you?" Aeschines never contributed anything positive towards the state.

Demosthenes has proven himself to be the better patriot. There are

two traits that mark a solid citizen: honor and loyalty.

Demosthenes never renounced his loyalty to Athens and always chose honor.

SHORT PERORATION (p. 324):

Demosthenes appeals

to the Powers of Heaven to grant the citizens a better purpose and spirit.

Should that not be possible, Demosthenes asks for the destruction of the

unworthy and a speedy deliverance for those who remain.

Classical Greece

Philip II's Phalanx Formation

(with sarissa lances [6 m. long])

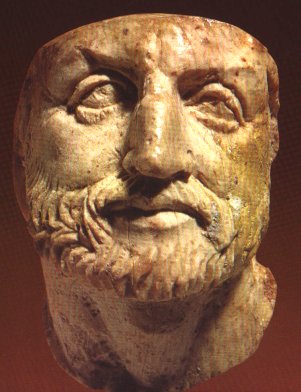

Philip II of Macedonia

|

Alexander the Great

|

Page created by

A. Robert Lauer

arlauer@ou.edu

12 Nov. 2014

|